The shadow over Obama’s Asia trip: 3 ways China scares the U.S.

President Obama is welcomed by South Korean President Park Geun-hye at the Blue House in Seoul, South Korea, on April 25, 2014. (Charles Dharapak/AP)

BY ISHAAN THAROOR

President Obama's ongoing tour through four Asian countries is a sign, we're told, of Washington's renewed effort to "pivot" or "rebalance" toward Asia. Far from conflict hot spots in the Middle East and now Eastern Europe, the Asia-Pacific is home to some of the world's most dynamic, exciting economies. As Obama's former national security adviser Tom Donilon wrote this week in The Washington Post, the administration is keen to move beyond the wars and occupations that "dominated U.S. national security policy and resources for the past decade" in favor of "a shift toward the region that presents the most significant opportunity for the United States."

But Asia is hardly a space free of contest. Obama's swing through Japan, South Korea, Malaysia and the Philippines — four democracies with warm ties to the U.S. — is a visit to allies who are, to varying degrees, wary of the rise of budding superpower China. Though U.S. officials repeatedly disavow claims that the U.S. seeks to "contain" China, Beijing appears to believe it and so do many scholarly observers. Here are three ways the specter of China looms large during Obama's Asia trip.

Balance of power in the Pacific: For decades, a Pax Americana, underpinned by U.S. naval supremacy, has authored the status quo in Asia. American military dominance is still a fact, but China's aggressive military expansion over the past two decades — its defense budget grew more than 12 percent this year alone — calls into question the long-term balance of power. Last year, China commissioned 17 new warships, more than any other nation. It aims to have four aircraft carriers by 2020 and has developed a considerable fleet of nuclear submarines. In the next few decades, China's ability to project naval power will extend deep into the South Pacific and Indian Oceans. (The Obama administration, in a thinly-veiled response, has committed to an expanded military presence in Australia and will work on a new security deal with the Philippines when in Manila next week.)

China's build-up comes alongside an increasing number of diplomatic spats between China and its neighbors over disputed territories, particularly islands in the South China Sea and East China Sea. Tensions with the nationalist government of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe over the Senkaku islands, known by the Chinese as the Diaoyu Islands, have flared dangerously in the past year, with Japanese and Chinese aircraft and vessels engaging in dangerously provocative maneuvers.

Calming Asia's troubled waters is no easy task, especially for an administration that wants to buttress traditional allies but remains fearful of antagonizing Beijing. Obama's mixed messaging in Tokyo was evidence of the awkward diplomatic tight rope he has to walk.

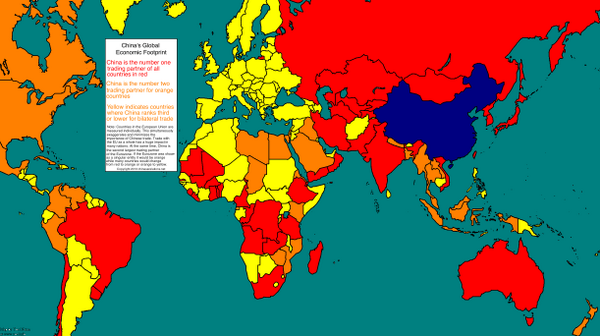

China’s global footprint: China is changing the game away from Asia as well. This year, China eclipsed the U.S. for the first time as the world’s largest trading nation. The map below, compiled by the Chinese Relations blog, shows the extent to which China has become the biggest trading partner of many countries in the developing world, particularly in Africa. (Note: It discounts the European Union as a single trading bloc for illustrative effect.)

Beyond trade, China is pouring billions of dollars into megaprojects around the world. Its state companies are building and investing in roads, mines, stadiums and dams from Papua New Guinea to Peru.

The growing scope of China Inc. — driven largely by China's insatiable appetite for natural resources — raises thorny questions about the future of global politics. Is Chinese influence in developing countries harmful for democracy? How does Washington deal with its declining clout in Latin America? Should we be concerned about a new form of Chinese neo-imperialism? The Obama administration's desire to fast-track the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal, a massive free trade pact that would knit together a host of countries around the Pacific, is in part aimed at reasserting American influence in a part of the world where it was once the unquestioned hegemon.

Friendship with Russia: It's no secret U.S.-Russia relations are in a bad place, with the West struggling to deal with Moscow's power play in Ukraine. Sanctions on Russian officials have been imposed and new rounds threatened as the Ukraine crisis worsens. But China, Russia's frequent collaborator on the U.N. Security Council, presents Russia with something of an escape. Recent reports suggest that the two countries may be close on a long-mooted natural gas deal worth billions of dollars. It's a deal that makes sense, especially if Russia wants to thumb its nose at Europe — currently the chief importer of Russian natural gas.

Russia and China are finding more reasons to deepen their political and economic ties, expanding trade and military links. For American strategists, they present a troubling axis of illiberal, authoritarian states that has already stymied U.S. objectives over a host of issues at the U.N., including the drive for tough action on Syria. At the same time, the U.S.'s democratic allies in Asia are finding more reasons to bicker — Abe's nationalist government in Japan has riled South Korea — while India and the grouping of Southeast Asian nations, ASEAN, show little to no inclination to help the U.S. hedge against China. The American "pivot" to Asia may be an escape from quagmires further west, but it comes with no shortage of headaches of its own.

Ishaan Tharoor writes about foreign affairs for The Washington Post. He previously was a Senior Editor at TIME, based first in Hong Kong and later in New York.

The Washington Post

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete